Has Google Made You Stupid? Has Linking Linked You Out?

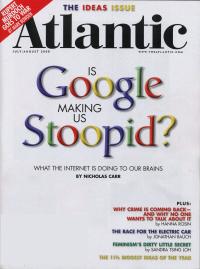

In the July, 2008 (bear with me, I know this was last decade) issue of The Atlantic, Nicholas Carr wrote an essay entitled “Is Google Making Us Stupid: What the Internet is Doing to Our Brains.” The essay was not only timely but spread fast across the internet—it became a key reference point for conversations revolving around cognition and the detriments inflicted upon it by an increasingly less attentive populace. At first, what shook me about the essay was not that it brought anything new to light; for years it has been obvious that with the progression of social networking platforms, online magazines, and just plain faster avenues of technology, our minds bolt even faster—up and over and left and right, and that the difficulty of concentrating is in part due to there being too many options for an elsewhere, too many vibrant and magnetic portals. What shook me was the fear of my own patience dwindling, or that I might lose out on the whole of an issue.

In the July, 2008 (bear with me, I know this was last decade) issue of The Atlantic, Nicholas Carr wrote an essay entitled “Is Google Making Us Stupid: What the Internet is Doing to Our Brains.” The essay was not only timely but spread fast across the internet—it became a key reference point for conversations revolving around cognition and the detriments inflicted upon it by an increasingly less attentive populace. At first, what shook me about the essay was not that it brought anything new to light; for years it has been obvious that with the progression of social networking platforms, online magazines, and just plain faster avenues of technology, our minds bolt even faster—up and over and left and right, and that the difficulty of concentrating is in part due to there being too many options for an elsewhere, too many vibrant and magnetic portals. What shook me was the fear of my own patience dwindling, or that I might lose out on the whole of an issue.

Let us consider, for instance, electronic links—when a link takes you to a new window and then in that window there are many other links and they are equally as enticing as the first, how far might you actually lead yourself (or be led) away from the thing you started with? Before long, the article you desire reading the most will take you to Kevin Bacon in quicker than six links. And what if you don’t want to get to Kevin Bacon? You will leave the last link not really knowing much about what you first set out to indulge in, or to learn about; a string of headlines will be all your memory can salvage. What will you have beyond a quick reference point, a tangential proof masked by a series of quips?

It took me a while to realize if such wandering posed problems or not and if so to what extent. At the time of reading the article I was teaching a basic English Composition course at Columbia College in Chicago. In fact, I used this article to engage my students in conversation in every course I taught, especially the courses dabbling with the visual aspects of rhetoric and the semiotic challenges in making society and its impacts something available for lexical articulation. I was particularly startled by how many students turned toward bland amalgams of apathy. This “revelation” wasn’t new to them, they didn’t fear what this “phenomenon” would do, they didn’t even pause to shudder when I asked them, “Do you think you’ll ever know more than a little about anything?” To me, this is what the essay pronounced: we link so often that we start thinking in links. We constellate too quickly, forgetting how to sit on a planet for a while—walking around a giant grocery store without a list. Yes, we are linked in, but then in again and into another platform.

In many fields (think PR, Wall Street, media editing) working in links seemingly provides a multi-tasking parade of efficiency. But doesn’t this expediency, in terms of thought and speech cast many traditionally advantageous and immersive activities to the wayside? Just as book reading has slackened in favor of the laptop and Kindle there is also something being lost in the great but exhausted arena of conversation; that something is the ability to talk one thing out, or to “stick to the point.” Instead, things risk getting talked through, and quickly so. For example, consider watching a half-hour program that has a news bar at the base. The news bar shows the score of the game you wanted to see and it provides a headline for the event that you want to know more about it—this would be the talking through instead of the talking out. We are often flooded with a type of listening that operates out of bumbling digressions, clumsy vagaries, and splotchy verbiage. Yet let me slow down.

What is said above is only part of my initial impression. I now regard what at first worried me as a reminder of how fast we evolve: adapting to an interlinking stream of communication is both necessary and, in many fields, imperative to progression. Carr’s essay, which is polarizing at times, operates without too many links and allows for conversation—the “something” I was so afraid of losing upon first read. When given the task to read this essay, the majority of my students came back very willing, very ready to talk. The conversation led to what some students called the “video-game mindset”—he or she who is moving not only in and out of space but also swiftly through ideas and conversations; because of the glittery allure of other streets of thinking, roads of pondering, we skip the base. It took an essay highlighting this phenomena to allow the class to speak about one thing for a long period and even that one thing had its many “links.”

It becomes easier to link and link again because more information on a wider scale of topics can be taken in, referenced, and then catalogued. Coincidentally, it is this very human capability to link and reference many things that social media relies and advances upon. That cannot be argued. That is what I had to realize before I reacted too harshly to the conversation, before I became too hooked on some romantic idea or implausible request for those around me to sit still and talk about something that, despite societal or philosophical merits, is simply too heavy for excitement, too fleeced for patience. I needed to realize that the human’s capability to link is good for social media but also note that social media also tries hard to target this capability, thus the risk of losing “conversation” is still real.

Despite an acceptance of our thinking in links, I still think it’s possible to at times pause and talk one thing out. Yes, the majority of our days are spent talking things through, seeing things get talked through (newspapers, television, subway ads, etc.) and even thinking through topics, yet being conscious of this, and choosing to occasionally take one topic into a sustained dialogic space, is the reason conversations and sitting down to a good meal with friends or family can be so gratifying—conversations are had that bloom in one space, that hold a moment down before it’s been shuttled off to page nine, paragraph six, or tweet seven, link four. What Carr’s essay does best is gets us to slow down for a second and discuss how fast that we’re going. That we are moving faster and linking even more may not be a problem but if we fail to acknowledge that we do it, that we’re really good at it, we might link ourselves right out of our own ability to discuss near anything—even, perhaps, the weather. ![]()